HONEST DESIGN

ADC Talk 2019

Words tell us a lot about the times we live in. As designers, one wouldn’t think that words influence our work. However, I encountered many words in my career that, sometimes overnight, sometimes slowly, showed up and wholly changed my practice. There is a new group of words that invite themselves into almost every meeting for the last few years now: ‘sustainable,’ ‘transparent,’ and ‘ecological’ which are consequentially followed by ‘honest.’ For the first few meetings, I felt like a spectator, watching my clients dealing with these words like it was an uncomfortable, itchy sweater. The first group of words, ‘sustainable,’ ‘transparent,’ and ‘ecological’ named a shift that often was not in place yet and for most companies, admittingly are often really difficult to do so. So they were rarely uttered with confidence and mostly in open-ended sentences.

It took a bit until I realized that what made me uncomfortable was the last word on the list: HONEST

The task of the creative industry is to give form and, in my case, visualize more or less abstract topics. To render the intangible tangible. Confronted with the task to make, e.g., ‘sustainability’ real, I felt the itching myself. Rendering a car more appealing in a brochure than it is in your garage never created these feelings. Even when I portrayed lonely old people to be happier than they probably really are, no internal flags went up.

Now I knew how my clients probably felt, and I started wondering at which point our work created an honest representation of eco-responsible intentions or engagements. And on a much larger scale: Can a profession whose primary purpose is to seduce customers into consumption even be honest?

In different circumstances, this question was raised before: Viktor Papanek requested «Design for the Real World» in the 1970s, Tibor Kalman called out designers «being bad» when not challenging their irresponsible clients in the 1980s and Dieter Rams stated that» good design is honest design».

So... I have a few questions:

Is Honest Design part of our culture?

If we look at the history of art and design, wasn’t it always used to render the intangible tangible? The power of art and design is the capacity to condense complex ideas into one simple image. Religions would never have had their impact without the powerful artistic visualizations of abstract concepts in paintings and architecture (Pontelli, Michelangelo e.g.). Religious art and architecture are awe-inspiring feats that nobody who ever visited the Siena Cathedral can deny. Would religion have had the same success without these creative achievements? In the context of the dark and middle ages, would churches have had the same appeal if they would have been just four stone walls with a wooden cross?

Is the consumer even ready for Honest Design?

We all know that every car covers the need for basic transportation, and every bottle of water will hydrate us. However, we want the freedom to choose one brand story over another and incarnate the image and benefits of the particular brand story.

Can the ego of a designer stand Honest Design?

It’s not only the consumers that fuel these mechanisms, but also the designers. Almost every object already exists in it’s most ergonomic design. Think chairs or lemon presses. To quote Dieter Rams in full: «Good design is honest. It does not make a product more innovative, powerful, or valuable than it really is. It does not attempt to manipulate the consumer with promises that cannot be kept.»

So this means that a lemon squeezer should actually squeeze lemons. Whoever tries this with Philip Starck’s design will realize that squeezing lemons is only one part of the process - having the juice without the lemon seeds in a container is the other.

Does Honest Design depend on context?

It is part of design and fashion to be inspired by topics and themes. These often purely stylistic elements do not forcibly serve any purpose. If you take a military vehicle designed for combat, the design itself can be sincere and even successful in the military context it was created for. The same car in rural streets might turn a successful design into a hazard for pedestrians and the planet because it was initially not designed for this context. The SUV model Hummer as an adaption of the military Humvee is an example of this.

Are visual metaphors Honest Design?

Visual metaphors are often used to illustrate concepts. We see this often on product packaging, where craft paper textures are used to imply authenticity. These visual cues try to suggest an industrially produced product is actually as good as artisanal or homemade products. Using a digital font in a personal handwriting style for unlimited reproduction is another example where the signified is at odds with the actual object.

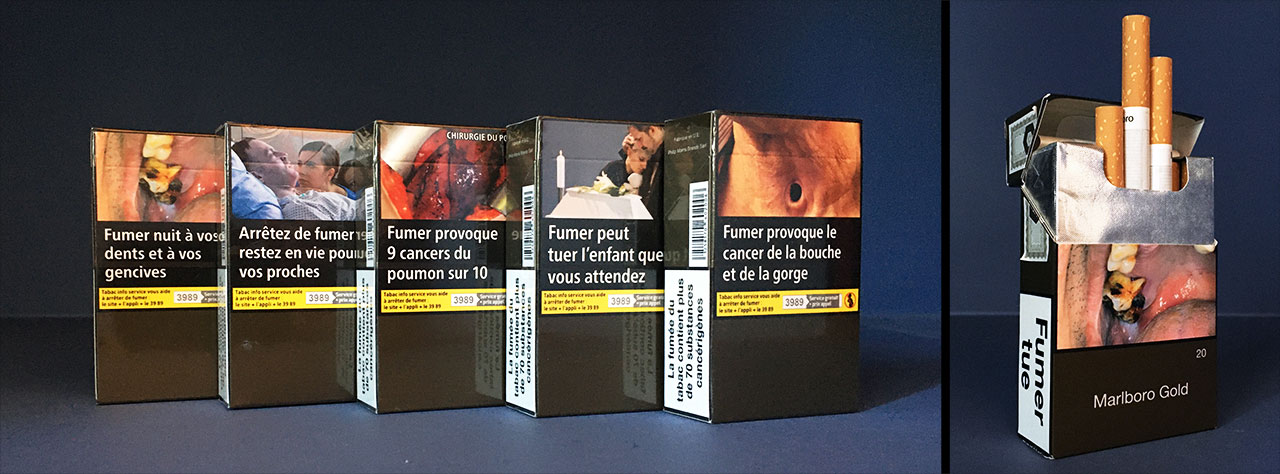

Is there too Honest Design?

However, when products are portrayed by the harm and problems they can create, we quickly drift off in a very dark world.

Does Honest Design need designers?

And if design was completely honest and purpose-driven, it might not even need designers. Many brands are using regular people instead of models and celebrity brand ambassadors.

Conclusion

What we are seeing is a power shift from the brand to the consumer. People want to know where product ingredients come from, where, how, and by whom under which conditions they are made. They want to be informed about the impact it may have on them and the planet.

Design can not be honest if the products and companies behind the brands are not ready for complete transparency and to adjust their products and services accordingly. The purpose of the designer places her/him between brands/products and consumers. This position allows designers to function as catalysts between the two. In practice, this means that designers need to transform the top-down hierarchy of design projects into a more collaborative approach to help to accommodate this change.

Honesty is not a design decision, it's a brand attitude and behavior

more projects...

RungisBranding

KoumkwatBranding

LeocareProject type

Institut Paul BocuseBranding

ElanBranding

Metal Shutter HousesBranding

ODDO BHFBranding

Raise InvestmentBranding

COPYRIGHT 2020 MARTIN ISELT